Calligraphy: A Language Beyond Writing in the Geography of the Islamic World

Across the vast expanse stretching from the Indian subcontinent and Central Asia to Western Asia, the Arab world, and extensive regions of Africa, calligraphy has carved a singular place of distinction. In this geography, calligraphy has never been merely a tool for communication; it has served as a language of beauty, identity, and culture—a language in which meaning and form intertwine to create an experience that transcends mere reading and seeing. This art, with a power that crosses borders, invites both the eye and the mind into a unique aesthetic and intellectual encounter.

Calligraphy as a Carrier of Meaning

From the earliest days, calligraphy has borne sacred and cultural messages. The earliest Qur’ans were transcribed in the Kufic script, and the sanctity of the text imbued the calligrapher’s role with elevated significance. In this context, calligraphy became more than a medium for communication; it emerged as a conduit linking the human spirit with profound aesthetic and spiritual experience. Each letter, word, and composition carried layers of meaning and cultural resonance, transforming calligraphy into a vessel for both contemplation and visual delight.

Calligraphy as Artistic Form

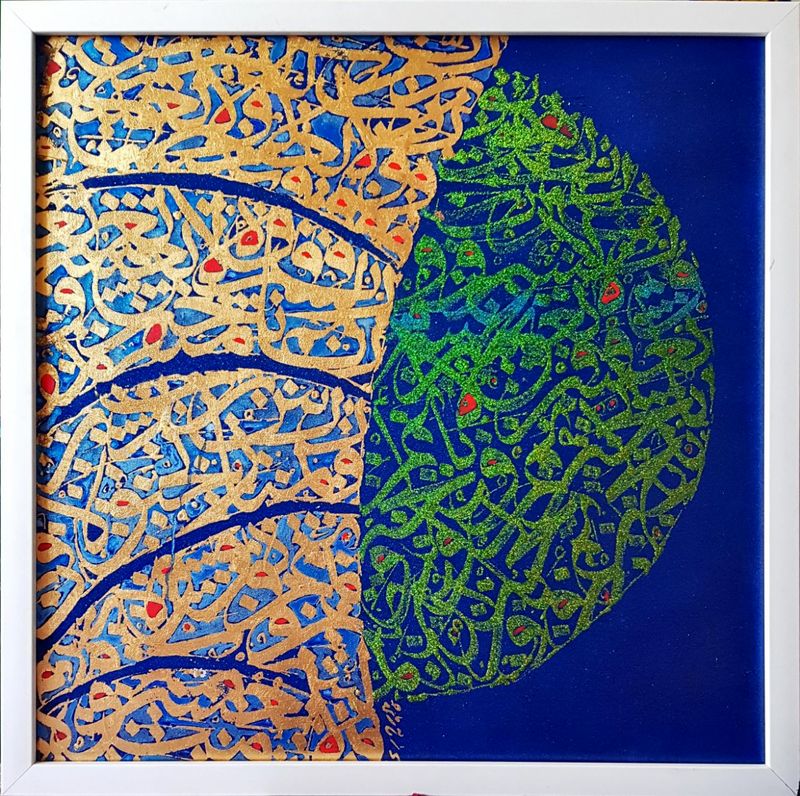

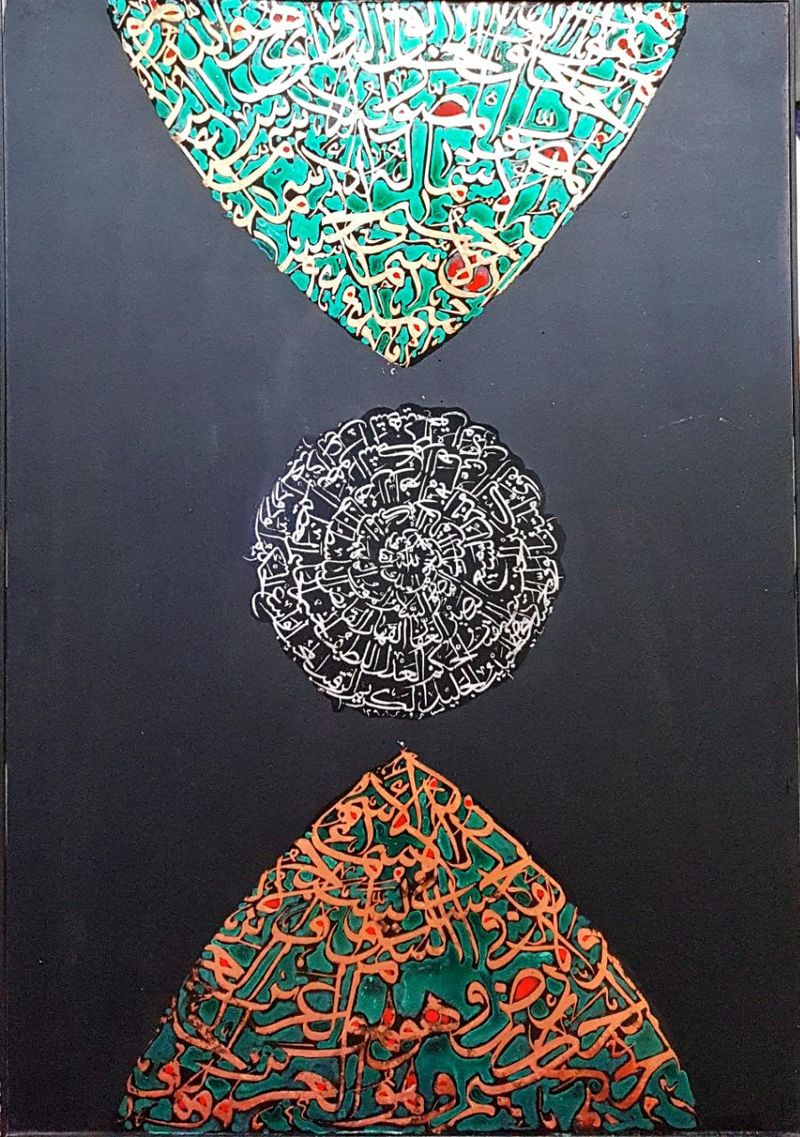

Calligraphy in this geography also ventured boldly into the realm of form and imagery. Scripts such as Muhaqqaq and Banna exemplify the integration of abstraction and geometry within Islamic art. Calligraphy adorned mosque walls, tiles, inscriptions, and even everyday crafts, where words themselves became images, transforming living spaces into stages of art. These abstract forms do more than please the eye; they engage the mind, inviting reflection and revealing new dimensions of harmony with each glance.

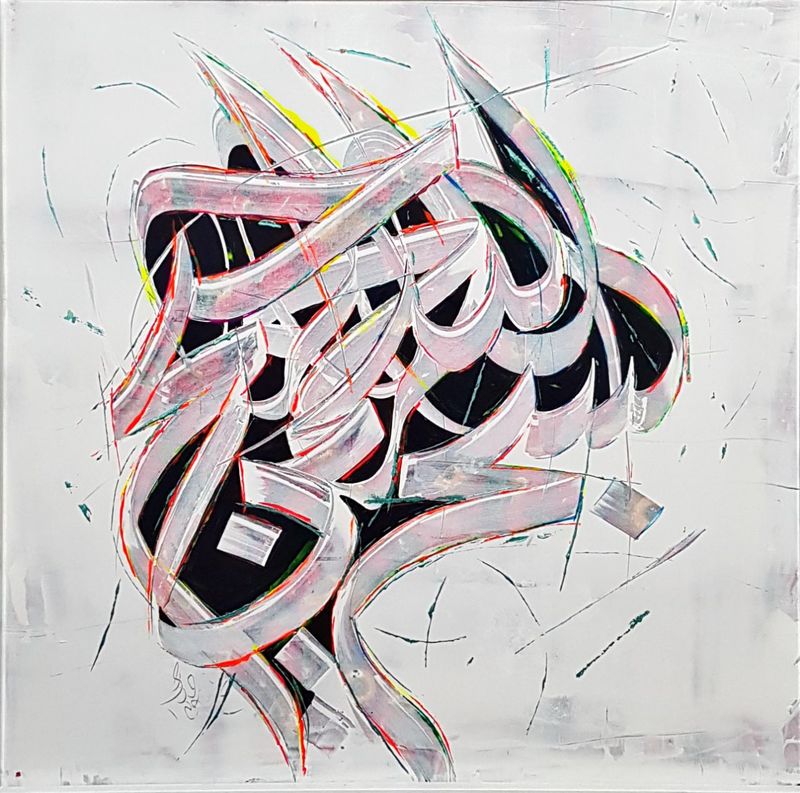

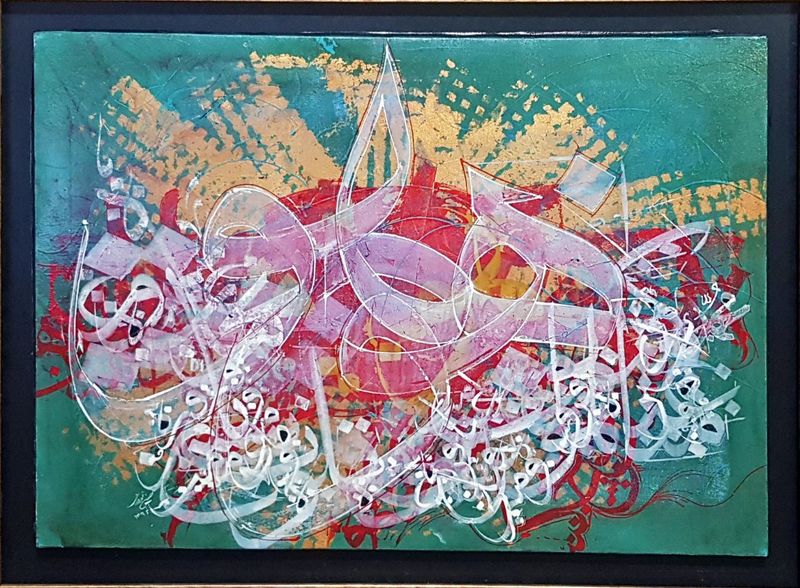

The Symbiosis of Meaning and Form

A defining feature of calligraphy in this region is the profound symbiosis between meaning and form. Scripts like Nastaʿlīq and Thuluth simultaneously convey textual messages and present themselves as visual compositions that delight the eye and spirit. In contemporary calligraphic painting, this symbiosis sometimes favors form over explicit meaning, with the text's semantic content subtly embedded within abstract beauty, encouraging viewers to explore and discover anew. This fusion of linguistic meaning with rhythm and motion has rendered calligraphy a multidimensional and all-encompassing art.

Calligraphy and Cultural Identity

Within the geography of the Islamic world, calligraphy has become a visual signature of identity. If painting and sculpture are central to the arts in the West, calligraphy has played an analogous role in these lands. A mosque without inscriptions or a Qur’an without calligraphy seems incomplete. Calligraphy is deeply intertwined with architecture, urban spaces, and public realms, and its presence in decorative arts, manuscripts, carpets, and textiles attests to its cultural centrality. Calligraphy has consistently reflected collective identity, transmitting history, ethics, and beliefs through its visual language.

Continuity in the Modern Era

With the passage of time and the advent of modernity, calligraphy has been revitalized. Avant-garde artists in Iran, Turkey, and the Arab world have introduced calligraphy into contemporary art discourse. Calligraphic painting has emerged as one of the most significant currents in contemporary art, attracting a global audience. These artists’ works demonstrate an inexhaustible capacity for combining form and meaning, each piece embodying a dialogue between tradition and innovation, engaging both the eye and intellect.

Global Comprehension of Calligraphy

The principles and concepts inherent in calligraphy are fully intelligible and applicable within Western aesthetic discourse. Rhythm, geometry, abstraction, and composition are all values recognized and appreciated by Western theorists, who have often drawn inspiration from them.

Calligraphy of the Islamic world provides precise methodologies for understanding form, space, and artistic expression—insights that have been studied, respected, and applied globally.

Inspiration for Western Art

Modern and contemporary Western art has repeatedly drawn upon this heritage, from the abstract movements of the twentieth century to conceptual and interdisciplinary practices. The presence of Islamic calligraphy in Western art attests to the universality of this tradition and its capacity to establish a shared artistic language across cultures. The interplay of meaning and form, rhythm, and geometric elegance has inspired Western artists in their exploration of space, movement, and composition.

And the Conclusion

From its earliest inscriptions to the works of contemporary innovators, calligraphy in the geography of the Islamic world has traveled a luminous and honorable path, consistently transcending mere textual representation. Avant-garde artists have reinterpreted traditional scripts, introducing them into global art discourse. Their works are featured in prestigious international auctions—from Christie's and Sotheby's to major European and American markets—where they command extraordinary prices. Substantial investment from the Arab world further attests to their value. Major contemporary museums in New York, London, and other cultural capitals proudly collect works by these artists, continuously acquiring and preserving them. This trajectory demonstrates that calligraphy and its modern adaptations constitute not only a heritage of identity and culture but also a global artistic asset. And the conclusion: calligraphy is a living, flourishing, and inspiring legacy—an art form that preserves its cultural roots while asserting a brilliant presence within modern and contemporary global art, becoming one of humanity’s most remarkable artistic achievements.

Hossein Norouzi – Researcher in Art Studies

Send Comments