Revealed: Europe’s Water Stores Rapidly Declining Amid Climate Breakdown

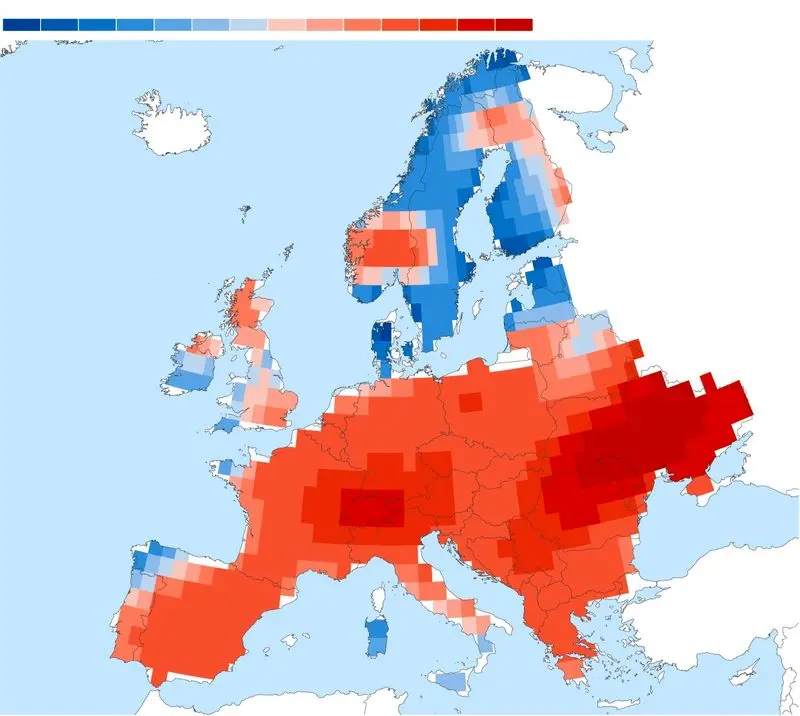

Rokna Political Desk: Fresh satellite data spanning more than two decades reveals a dramatic decline in Europe’s freshwater reserves, with vast regions of southern and central Europe rapidly drying due to accelerating climate breakdown—an alarming trend scientists say should serve as a decisive wake-up call for policymakers.

UCL researchers warn that major parts of southern Europe are drying out, with consequences described as “far-reaching.”

According to Rokna, a new analysis drawing on more than twenty years of satellite observations shows that extensive portions of Europe’s water reserves are rapidly diminishing, with freshwater resources shrinking across southern and central regions—from Spain and Italy to Poland and parts of the United Kingdom.

Scientists at University College London (UCL), in collaboration with Watershed Investigations and the Guardian, examined satellite data from 2002 to 2024 that captures variations in Earth’s gravitational field. Because water mass affects gravity, changes in groundwater, rivers, lakes, soil moisture, and glaciers appear in the signal, allowing satellites to effectively “weigh” Earth’s stored water.

The results reveal a striking imbalance: northern and northwestern Europe—particularly Scandinavia, parts of the UK, and Portugal—have been experiencing wetter conditions, while vast areas in the south and southeast, including regions of the UK, Spain, Italy, France, Switzerland, Germany, Romania, and Ukraine, have been steadily drying.

Scientists say the data clearly reflect climate breakdown. “When we compare total terrestrial water storage with climate datasets, the trends align closely,” said Mohammad Shamsudduha, professor of water crisis and risk reduction at UCL. He described the findings as a “wake-up call” for policymakers who remain hesitant about reducing emissions. “We are no longer discussing limiting warming to 1.5°C; we are probably moving toward 2°C above preindustrial levels—and we are now seeing the consequences.”

Doctoral researcher Arifin separated groundwater storage from the overall terrestrial water data and found that trends in these more durable water sources matched the broader pattern, confirming that much of Europe’s concealed freshwater supplies are being depleted.

The situation in the UK is mixed. “Overall, the west is becoming wetter while the east is getting drier—and that pattern is intensifying,” Shamsudduha said. “Even if total rainfall remains steady or slightly increases, the distribution is changing. We are seeing heavier downpours and longer dry periods, especially in summer.”

Groundwater is considered more climate-resilient than surface water, but intense summer storms often cause water loss through runoff and flash flooding, while winter recharge periods may be shortening. “In southeast England, where groundwater provides around 70% of public water, these shifting rainfall patterns could create serious challenges,” he warned.

European Environment Agency data show that overall water extraction from surface and groundwater sources across the EU fell between 2000 and 2022, but groundwater withdrawals rose by 6%, driven by public water supply (18%) and agriculture (17%). Groundwater is vital: in 2022, it accounted for 62% of public water supply and 33% of agricultural demand across member states.

A European Commission spokesperson said the EU’s water-resilience strategy is designed “to help member states adjust their water-resource management in response to climate change and human-driven pressures.” The strategy aims to create a “water-smart economy” and is accompanied by a recommendation on water efficiency that urges at least a 10% improvement by 2030. With leakage rates ranging from 8% to 57% across the bloc, reducing pipe losses and upgrading infrastructure are seen as essential steps.

Hannah Cloke, professor of hydrology at the University of Reading, said: “It’s deeply concerning to observe this long-term trend. We’ve experienced major droughts recently, and we keep hearing that this winter may bring lower-than-normal rainfall while we are already in drought conditions. Next spring and summer, if rainfall falls short, there will be severe consequences here in England. We will face strict water restrictions that will significantly disrupt daily life.”

The Environment Agency has already warned that England must prepare for drought conditions extending into 2026 unless substantial rainfall occurs during the autumn and winter.

Water minister Emma Hardy said there is “mounting pressure on our water resources,” noting that the government is taking “decisive action,” including plans for nine new reservoirs to bolster long-term resilience. But Cloke cautioned that merely “promising very large reservoirs that won’t be operational for decades” does not address the immediate crisis. “We should focus on water reuse, reducing consumption, separating drinking water from recycled water that could be used elsewhere, adopting nature-based solutions, and reconsidering how new developments are constructed. We are simply not moving fast enough to keep pace with these long-term shifts.”

Shamsudduha warned that Europe’s drying trend will have “far-reaching” effects, striking food security, agriculture, and ecosystems dependent on water—especially habitats fed by groundwater. Spain’s declining reserves, he noted, could directly affect the UK, which depends heavily on Spanish and other European produce.

Impacts long associated with the global south—from South Asia to Africa and the Middle East—are now “much closer to home,” with climate change “unmistakably affecting Europe itself.” Shamsudduha called for improved water management and openness to “new, even unconventional” approaches, including widespread rainwater harvesting in countries such as the UK.

Globally, hotspots of drying are forming across the Middle East, Asia, South America, the U.S. west coast, and large parts of Canada, with Greenland, Iceland, and Svalbard also showing significant drying trends. In Iran, Tehran is approaching “day zero,” when no tap water remains available, prompting plans for water rationing. President Masoud Pezeshkian has warned that if rationing fails, the capital may have to be evacuated.

Send Comments