From Organ Transplants to Eternal Life: Analysis of the Mysterious Conversation Between Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin

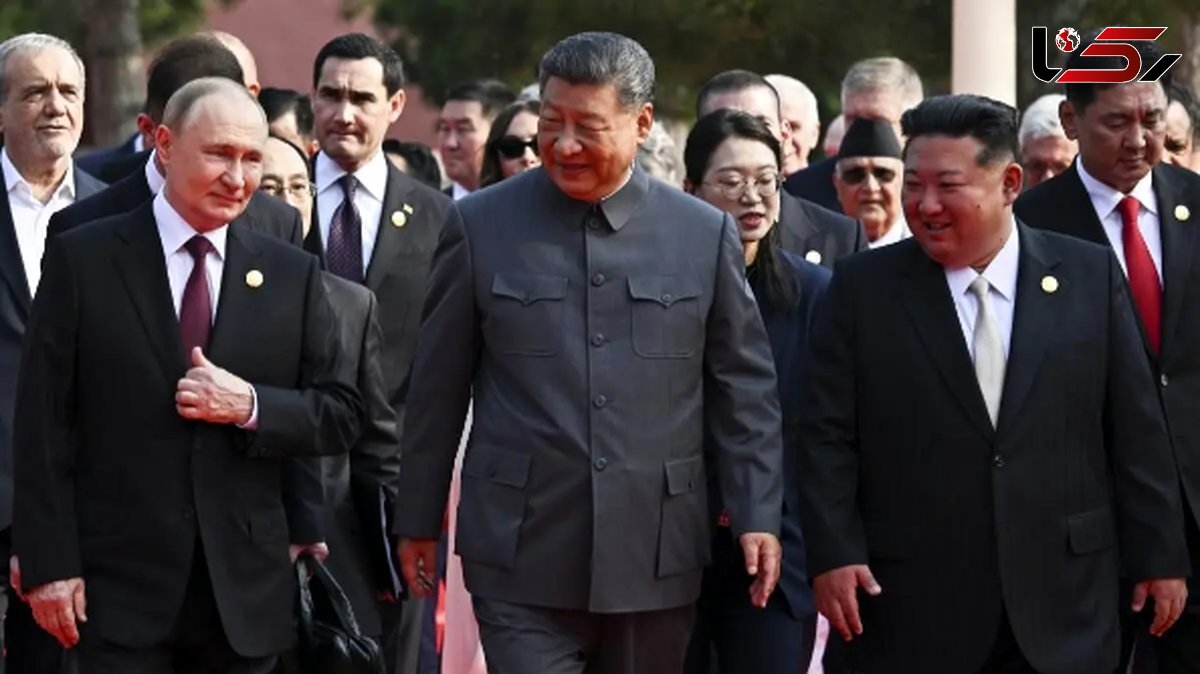

Rokna Political Desk: A confidential conversation between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin about organ transplants and the possibility of extending human lifespan was inadvertently revealed during a military parade in Beijing.

Could organ transplants make immortality possible? This unexpected topic arose this week during the meeting of Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin at a military parade in Beijing.

According to the BBC, an interpreter translating Putin’s words into Mandarin explained to Xi that human organs could be transplanted multiple times “to make a person younger and younger,” and perhaps even “forever” prevent aging.

He added, “It is predicted that in this century, it may be possible to live up to 150 years.”

The smiles and laughter of the two leaders suggested the conversation was partly in jest, but could they have been pointing to a noteworthy scientific consideration?

Organ transplants undoubtedly save lives, but the surgeries are complex and highly risky.

According to the UK National Health Service’s Blood and Transplant division, over the past 30 years, organ transplants have saved the lives of more than 100,000 people.

During the parade, while a microphone was inadvertently left on, Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin discussed the potential use of organ transplants to extend human lifespan.

Organ Transplants for Eternal Life: Was There a Clue in the Xi-Putin Conversation?

Continuous advancements in medicine and technology mean transplanted organs can function longer within recipients’ bodies. Some kidney recipients have maintained organ function for over 50 years.

The lifespan of a transplanted organ depends on the health of both the donor and recipient, as well as the level of care provided. For instance, a kidney from a living donor may last 20 to 25 years, whereas one from a deceased donor may last 15 to 20 years.

The type of organ is also significant. According to research published in the Journal of Medical Economics, a liver may last around 20 years, a heart approximately 15 years, and lungs close to 10 years.

Putin and Xi may have discussed multiple or repeated organ transplants. However, each surgery carries significant risks. Patients receiving new organs must take lifelong potent immunosuppressive drugs, which can cause high blood pressure and increase susceptibility to infections. Organ rejection—when the immune system attacks the transplanted organ—can occur even with medication.

Custom-Made Organs

Scientists are working on genetically engineered pigs as organ donors to reduce rejection risks. Using CRISPR gene-editing technology, they remove certain pig genes and introduce specific human genes to make the organs more compatible with human bodies. These specially bred pigs are ideal because their organs are approximately human-sized.

This science remains experimental; to date, only one heart and one kidney transplant using this method have been performed. The two men who underwent these procedures were the first volunteers in this new branch of xenotransplantation. Both later died, but their participation advanced the field of cross-species organ transplantation.

Another avenue under investigation is growing fully functional organs using human cells. Stem cells can transform into any type of cell or tissue in the body. No research group has yet produced a fully transplantable human organ, but scientists are gradually approaching this goal.

In December 2020, British researchers at University College London and the Francis Crick Institute regenerated a human thymus—a vital organ for the immune system—using human stem cells and a bioengineered scaffold. When transplanted into mice for testing, the organ appeared functional.

Researchers at London’s Great Ormond Street Hospital have also grown human intestines from stem cells derived from patient tissue, a process that could eventually lead to personalized transplants for children with intestinal failure.

However, these advances are aimed at treating diseases, not extending human life to 150 years.

Meanwhile, technology entrepreneur Bryan Johnson spends millions annually attempting to reduce his biological age. To date, he has not received a new organ, though he injected plasma from his 17-year-old son into his own body. He later stopped, having seen no measurable effect and facing regulatory scrutiny from bodies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Dr. Julian Motz of King’s College London noted that beyond organ transplants, experimental techniques like plasma replacement are being studied, but their meaningful impact on human lifespan—especially maximum lifespan—remains uncertain, though the field is attracting considerable scientific attention.

Professor Neil Mabbott, an immunopathology expert at the Roslin Institute, University of Edinburgh, believes the human lifespan may have an upper limit of around 125 years. He told the BBC, “The oldest verified individual was Jeanne Calment of France, who lived from 1875 to 1997 and died at 122 years old.”

He explained that while damaged organs can be replaced, aging bodies become increasingly less resilient and struggle to cope with physical stress. “Our immune response weakens, bodies become more fragile and injury-prone, and repair and recovery capacities diminish. Stress, surgical trauma, and lifelong immunosuppressive medication for transplant rejection would be too harsh for patients at extreme ages.”

Professor Mabbott concluded that rather than striving solely for longevity, the focus should be on living healthier years. “Living much longer while suffering multiple age-related diseases and frequently visiting hospitals for repeat transplants does not seem an attractive way to spend retirement.”

Send Comments