Spokesperson for the National Water Industry Highlights:

Water Security Instead of Water Supply / The Need to Redefine Water Governance Responsibilities in Iran

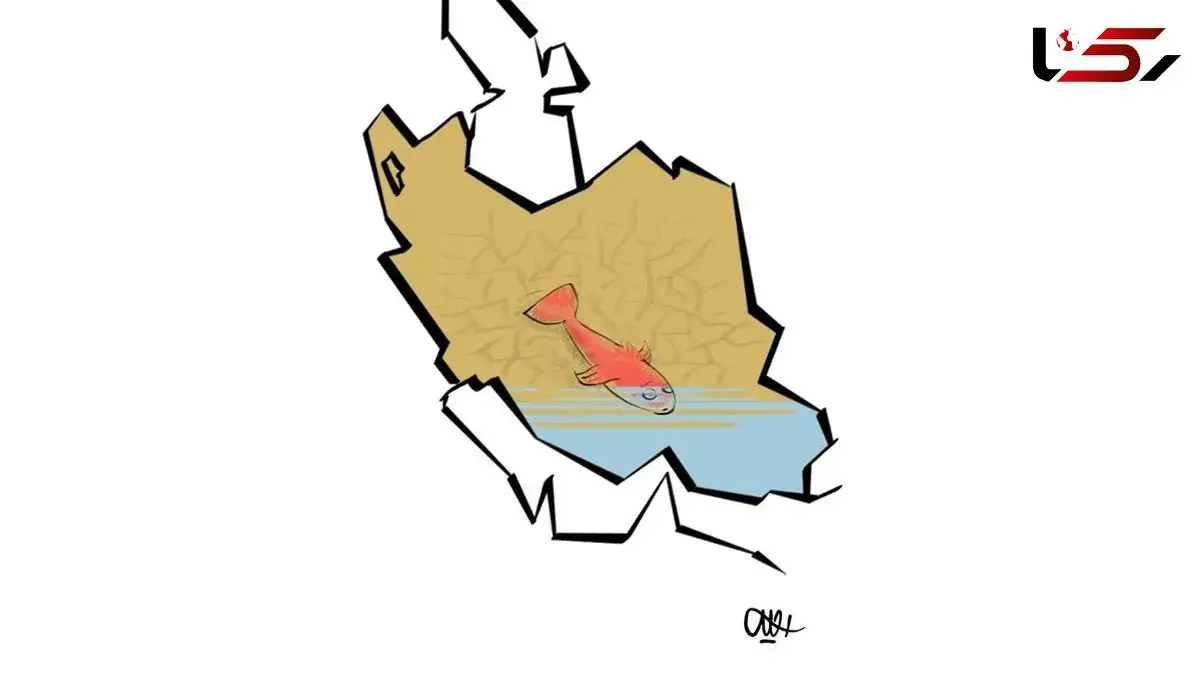

Rokna Economic Desk: The spokesperson for Iran’s water industry argues that the country’s water crisis is not merely the result of resource shortages, but rather the product of a rigid intellectual, institutional, and cultural mindset that interprets development as domination over nature and ignores the inherent complexity of the land. The solution, he says, lies in moving away from engineering-centrism and project-driven approaches toward participatory governance, epistemic humility, and a fundamental redefinition of the relationship between people and their environment.

Isa Be'zargadeh, spokesperson for the national water industry, stated: “The water crisis in Iran, beyond the shortage of a vital substance, reflects the retreat of wisdom and thought in the face of the complexity of natural and social systems. This crisis is a clear manifestation of dogmatism in the decision-making apparatus and demonstrates how mental maps have become detached from the land they claim to govern.”

The prevailing vision of development—understood as conquest of nature—has proven incompatible with the fragile climatic reality of Iran. From this disconnection emerges a triad of a closed mindset, locked-in institutions, and mythologized cultural patterns; three intertwined layers that restrain governance within the confines of rigid thinking. Overcoming this cycle is not achievable through a single technical measure, but only through a profound transformation in the nation’s epistemic system and collective imagination—one that reconnects public reasoning with the land itself.

Gregory Bateson warns that crises begin when mental maps disconnect from the land, and the Iranian experience in water and development is an exact embodiment of this idea; a mindset that perceives development as subjugation of nature inevitably fails in a land that is arid, fragile, and complex. Intensifying droughts, resource degradation, and climate change have deepened and entrenched this rupture.

At the heart of this divide, the triad of dogmatism emerges: a mind seeking certainty, an institution operating on repetition and fixation, and a culture that reproduces the myth of the “water-bringing hero.” But unlike its mythical counterpart, today this “hero” is no longer a farsighted steward and guardian of balance between humans and their land, but has transformed into a structure-focused engineer.

In the mental sphere, the “need for cognitive closure” described by Kruglanski pushes individuals toward the comfort of definite answers. In Iran’s water governance, this mental need has manifested as engineering-centrism—an approach that dismisses the complexities of social, economic, and ecological dynamics and replaces them with the illusion of certainty over intricate networks of interactions.

Confirmation bias reinforces this mindset: successes are amplified, failures minimized, and unintended consequences overlooked. Erich Fromm calls this unconscious inclination to seek refuge in certainty a “flight from freedom.” The closed mind arises not from ignorance but from fear—fear of confronting ambiguity and complexity. Faced with the confusion of the world, it seeks shelter in the arms of certainty.

Yet the mind is only one part of the puzzle; institutions reproduce and fortify this mindset. Pierre Bourdieu notes that the dominant discourse of every social field is shaped by the holders of symbolic capital. In Iran, the symbolic capital of engineering has become so deeply rooted that governance-oriented, social, or ecological approaches are marginalized as “non-technical”—as though technicality itself is the measure of truth.

This monopoly reflects the complex relationship between power and knowledge described by Michel Foucault: power is exercised not through commands but through defining what questions are legitimate. When the dominant question is “How can more water be supplied?” the foundational questions—reforming consumption patterns, managing demand, and rethinking governance—fade from consideration. Within this structure, governance drifts toward showcase development: large-scale mega-projects, despite their side effects, overshadow small but effective reforms because they offer greater visibility.

Culturally and mythologically, this trend is continuous. Mary Douglas reminds us that societies interpret the world through pre-established symbols and patterns. In Iranian culture, the myth of the “water-bringing hero” is ancient—from Kay Khosrow and the narratives of the Shahnameh to the anonymous engineers of qanats and the intricate irrigation networks built centuries before modernity, grounded in profound ecological knowledge and sustainability. The water hero was not a conqueror of nature but a guardian of balance between humans and the land.

In the modern era, however, this narrative has shifted, transforming the hero into a structure-focused engineer—an archetype in which domination over nature replaces prudence and equilibrium. This symbolic shift has also altered the role of the state, turning it from a regulator of complex relations into an executor of colossal showcase projects. James Scott calls this tendency to simplify reality “seeing like a state”: an inclination to view the world through broad, low-resolution, measurable schemes while overlooking local knowledge and nuance. Mythological imagination not only shapes the past but also the future, generating institutional self-fulfillment—an imagined future in which construction replaces governance and spectacle replaces sustainability.

Breaking this cycle requires a return to the principle of fallibility—the same epistemic humility emphasized by Karl Popper. Progress does not arise from absolute certainty but from accepting the possibility of error and embracing continuous improvement.

On the mental level, this transition requires moving beyond engineering-centrism toward interdisciplinarity: training experts who, while mastering their own fields, can engage in dialogue with the social sciences, economics, ecology, and politics.

On the institutional level, redefining the mission of water agencies from “water supply” to “water security” becomes essential—institutions capable of enabling independent evaluation, effective accountability, and a shift from theatrical achievements to real efficiency.

On the cultural level, redefining the water hero transforms them not into a builder of structures but into a facilitator of processes and social participation. Development in this sense is not a matter of adding to the length of tunnels or the height of dams, but of enhancing governance capacity and the ability to manage complexity.

Iran’s water crisis is, at its core, a crisis of knowledge, institutions, and culture—a self-reinforcing triad that drives decision-making toward destructive simplification. This cycle can be broken only when mental maps reconnect with the realities of the land; when epistemic humility, acceptance of plurality, and the courage to confront complexity replace the pursuit of certainty. The future of Iran’s water security lies in the path of an open, participatory, and intellectually engaged society—one in which collective wisdom and dialogue prevail over dogmatism, and in which land and people coexist in sustainable harmony.

Send Comments