Makeup: Design of the Face or Merely Feminine Adornment?

Makeup has long held a serious and sometimes ritualistic role across cultures. From the kohl-lined eyes of ancient Egypt to the use of plant-based pigments in Iran and India, makeup has served not only as a means of personal beautification but also as a cultural and social marker. Yet in today’s world, a new question arises: can makeup be considered a form of design?

To answer this, we must first clarify what design means. Design is far more than surface decoration. It is a conscious and purposeful process built upon principles of need, proportion, functionality, and aesthetics. Whether it is a poster, an interior space, or the visual identity of a city, design is guided by harmony, balance, color theory, and its impact on the audience. If we look closely at makeup, we realize it follows much the same logic.

Makeup is an art that reshapes the textures, lines, and colors of the human face. Choosing a lipstick shade to complement one’s skin tone, selecting eye shadow to match clothing, or balancing colors according to lighting and environment—these all reveal that makeup, like design, is an intentional composition. A woman applying makeup is not merely adding pigment; she is effectively redesigning the visual presence of her face, treating it as a living canvas.

Throughout history, however, ideals of beauty and makeup have constantly shifted. What was celebrated in one era could be rejected in another. In Qajar-era Iran, thick, dark eyebrows and rounded, full faces were prized. Beauty was enhanced with traditional tools: sorkhab (rouge) for rosy cheeks, sepidab (powder) for a pale complexion, and surmeh (kohl) to accentuate the eyes. These natural substances embodied the cultural aesthetics of their time.

With the arrival of modernity and global exchange, these values changed. Heavy traditional pigments gradually gave way to mascara, foundation, eyeliner, and an array of eye shadows and lip liners. Such products allowed for greater variety and established a kind of universal standard of beauty. Today, the line between Eastern and Western styles of makeup is blurred; multinational cosmetic brands have turned beauty into a shared global language.

Several factors influence these transformations. Culture is the foremost determinant: what one society sees as grace, another may dismiss as excess or even impropriety. Climate and environment also play a role: in warmer regions, lighter tones and subtle makeup are more practical, while in colder or darker climates, stronger pigments and bold contrasts prevail. Economic class has long been another factor; in the Qajar era, high-quality sorkhab or surmeh indicated wealth and privilege, just as luxury brands do today.

Thus, makeup extends beyond the personal sphere into the social one. A woman wearing makeup in public presents not only her face but a designed image of herself. This image may signal confidence, a desire for visibility, or adherence to fashion trends. Just as a graphic designer crafts a poster with an audience in mind, so too does a woman apply makeup with social perception in view.

In this sense, makeup can indeed be understood as a branch of design, its subject being the human face. It evolves with historical shifts, adapts to ecological conditions, and gains meaning within cultural and social contexts. It is a living form of design, because its canvas is the human face—dynamic, emotional, and ever-changing.

In our contemporary world, with the rise of global cosmetic industries and professional makeup artistry, this connection is stronger than ever. Makeup artists work much like graphic designers: mastering color, light, texture, and the psychology of the viewer. The only difference is the medium—one works on paper or digital screens, while the other works on living skin.

We may therefore conclude: makeup is not merely feminine adornment, but a form of design. A design that highlights individual beauty while also carrying cultural, historical, and social messages. A woman who applies makeup with awareness and subtlety is as engaged in the process of design as a graphic designer at his studio.

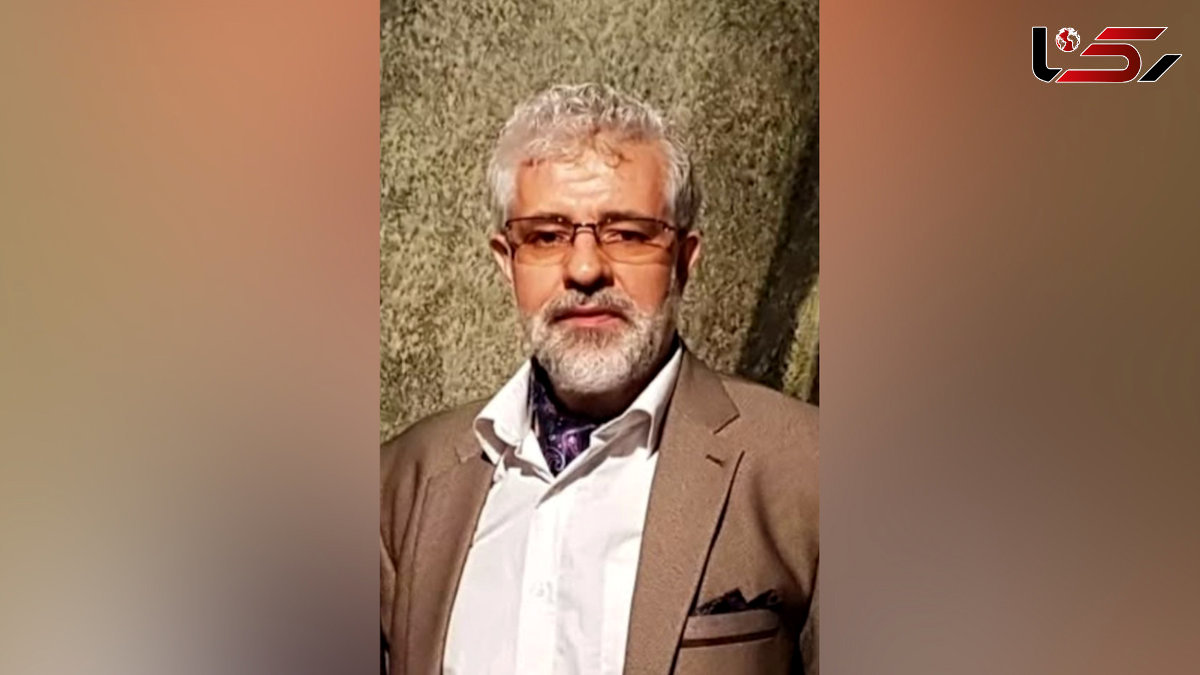

By Hossein Norouzi, Researcher in Art Studies

Send Comments