Visual Arts and Their Role in Creating Vitality and Dynamism in Contemporary Iranian Society

Contemporary Iranian society is entangled in a complex web of economic, social, and cultural crises that erode people’s psychological resilience and collective hope on a daily basis. Economic pressures, cultural restrictions, and the absence of a clear outlook have created a heavy atmosphere that often results in diminished collective energy and a growing sense of indifference. Under such conditions, the visual arts—particularly graphic design—can serve as an effective tool for reviving vitality and social dynamism. What makes this field especially significant is its direct connection to daily life. Graphic design permeates product packaging, environmental advertising, product design, and even urban landscapes. This constant presence transforms it into a social and psychological language capable of enhancing the quality of urban life.

Despite such potential, graphic design in today’s Iran remains underutilized. A simple look at the cityscape makes this clear: overcrowded and chaotic billboards, scattered signage, and inconsistent color palettes have turned urban environments into arenas of visual disorder. While many advanced cities manage design and advertising according to principles of visual harmony and cultural identity, Iranian cities rarely follow a coherent strategy. The result is psychological fatigue for citizens who face this disarray daily, receiving not energy and optimism but exhaustion and frustration.

Outdoor advertising, which could be an opportunity to combine cultural and economic values, has instead become a competition for instant attention. Ideally, billboards and advertising structures should not only introduce products but also convey cultural, educational, or social messages that contribute to a positive urban identity. In practice, however, they often bombard the public with repetitive images and slogans, draining rather than inspiring the collective psyche. The absence of a cultural perspective in outdoor advertising reduces cities to commercial, unartistic spaces, even though such media could serve as platforms for inspiration and public engagement.

Product packaging is another example of this shortcoming. In many countries, packaging functions as part of national identity and even as an instrument of cultural diplomacy. Japan and South Korea, through innovative design and meticulous attention to detail, have succeeded in projecting a modern, trustworthy image of their products. In Iran, although many young and creative designers are producing valuable work, a large portion of domestic goods are still presented with stereotypical or low-quality designs. This not only weakens the competitiveness of Iranian products in global markets but also signals disregard for consumers at home. A poorly designed package communicates indifference to the buyer—even when the product itself is of high quality.

A review of Iranian graphic design history reveals that this field has often been overshadowed by politics and economics, with little chance to flourish independently. From the artistic and cinematic posters of the 1960s and 1970s to the commercial advertising of recent decades, graphic design has been treated primarily as an instrument rather than an autonomous practice. Efforts such as urban mural painting, cultural posters, and art festivals have occasionally injected moments of creativity and hope into public spaces. Yet these initiatives remain fragmented and rarely evolve into a sustainable system. In many cases, they are confined to symbolic projects that fail to leave a lasting impact on the urban landscape or the everyday life of citizens.

The importance of graphic design in generating social vitality lies in its connection to human perception. Images, colors, and forms exert direct and unconscious effects on the mind.

Just as visual chaos can create anxiety and depression, harmony in color and well-crafted design can foster optimism, calmness, and collective motivation. In other words, every poster, package, or billboard carries a psychological message that influences social behavior, either strengthening or weakening collective energy.

To harness this capacity, several key measures are necessary. First, establishing unified urban design management to restore visual harmony to cities. Second, creating structural support for graphic designers and providing professional spaces that encourage creativity. Third, paying serious attention to packaging design as a sign of respect for consumers and an enhancement of the domestic market. Fourth, adopting a more thoughtful approach to outdoor advertising—one that integrates commercial messages with cultural and social values. Such measures could gradually transform urban landscapes into more pleasant environments and highlight the role of art in everyday life.

Ultimately, it must be emphasized that graphic design and visual communication in Iran today are not artistic luxuries but social necessities. This field has the capacity to reshape cityscapes, reduce citizens’ psychological fatigue, and return a weary society to a state of hope and dynamism. Such a vision can only be realized if our perspective on graphic design shifts—from seeing it merely as a tool for selling products to recognizing it as a language for better living and a more dynamic future. If the visual arts, particularly design and graphics, find their rightful place in urban and economic planning, then it is possible to hope that vitality and creativity will become lasting elements of collective life in Iran.

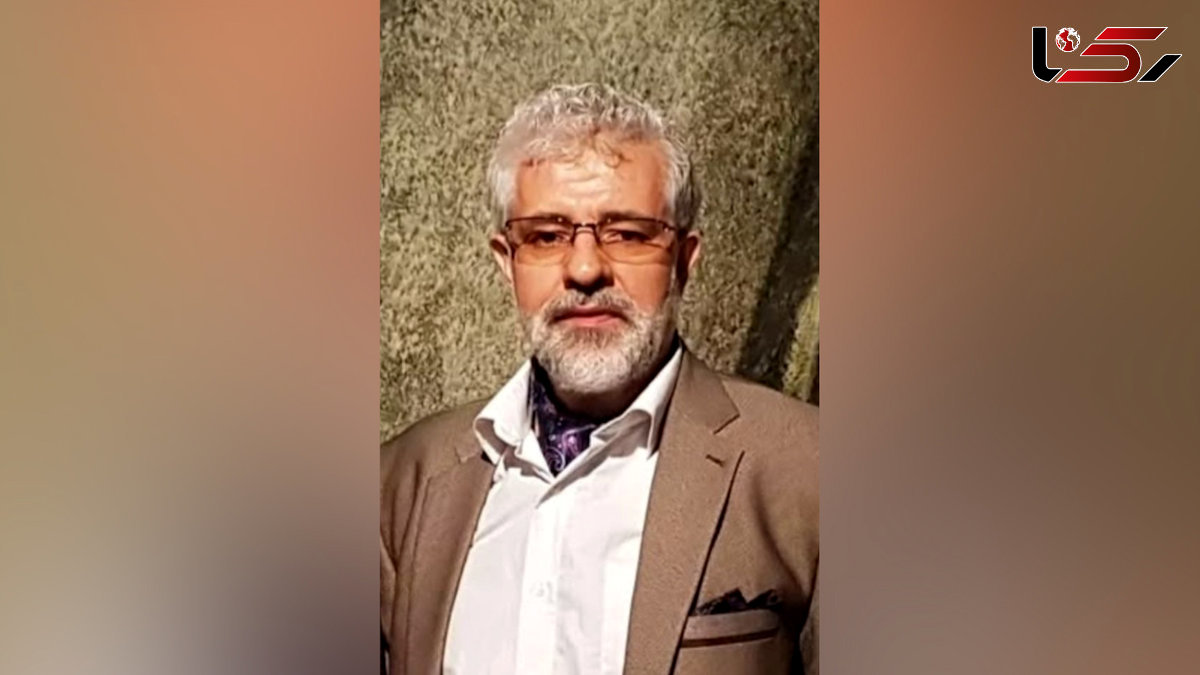

Hossein Norouzi – Researcher in Art Studies

Send Comments